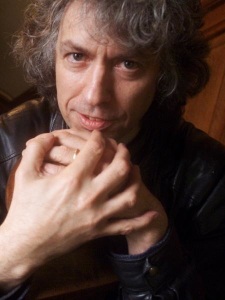

This week saw the tragic passing of playwright and NHB author Stephen Jeffreys. Known for works including hit historical romp The Libertine, he was also a caring and supportive mentor to an entire generation of writers. In this edited introduction from a recently published collection of Stephen’s plays, his wife, Annabel Arden, pays tribute to the life and career of a much-loved figure. Plus, publisher Nick Hern shares a few words on a man he was proud to not only call an author, but a friend…

This week saw the tragic passing of playwright and NHB author Stephen Jeffreys. Known for works including hit historical romp The Libertine, he was also a caring and supportive mentor to an entire generation of writers. In this edited introduction from a recently published collection of Stephen’s plays, his wife, Annabel Arden, pays tribute to the life and career of a much-loved figure. Plus, publisher Nick Hern shares a few words on a man he was proud to not only call an author, but a friend…

Stephen Jeffreys was born on April 22 1950 and spent his childhood in Crouch End, North London. His father’s family ran a business making billiard tables, where he himself spent a short time working after university and which he immortalised in his play A Going Concern. According to family legend his great-grandfather taught the Pankhurst sisters how to play billiards. His mother’s family were originally from Ireland. The house Stephen grew up in, 45 Weston Park, had been acquired by his paternal grandfather in 1936, and three generations as well as many lodgers lived there in a very particular post-war austerity. It was a childhood full of eccentric characters, English humour and stoicism. His monologue Finsbury Park (commissioned by Paines Plough for their 2016 series of Come to Where I’m From, and performed by Stephen himself) captures the essence of this. The house remained inhabited by his sister, the writer and journalist Susan Jeffreys, and Stephen later returned to share it with her, bringing myself and his two sons Jack and Ralph to this almost mythical extended family home. It was known to all as ‘The Chateau’.

Finsbury Park by Stephen Jeffreys was part of Paines Plough’s Come to Where I’m From project

Stephen was educated in Crouch End, at Rokesly Primary School, and then at a boys’ grammar, the Stationers’ Company’s School in Hornsey, before going to read English at Southampton University. While there he revitalised the student theatre scene and took a company to the Minack Theatre in Cornwall, directing Indians, in which he cast all the Indians as women – an idea ahead of its time and setting the trend by which he gave great parts to women in all his plays. After his short spell in the family business and work as a supply teacher, he wrote Like Dolls or Angels, taking it to 1977 National Student Drama Festival, where it won the Sunday Times Playwriting Award. Later he would join the board of the NSDF, which he served on for many years.

A part-time job teaching theatre in an art college in Carlisle gave him time and solitude to write, as well as the experience of putting on enormous community plays combining street theatre with carefully staged disruption and spectacle, such as The Garden of Eden (1986) about nationalised beer performed by the people of Carlisle. While living in Carlisle he also spent time at the Brewery Arts Centre in Kendal, where he met Gerry Mulgrew, Alison Peebles and Robert Pickavance, who would go on to found Communicado. Together with Stephen they formed Pocket Theatre Cumbria, which toured the north.

Round this time, Stephen decided to devote his talents to writing plays. His first big success came in 1989 when Valued Friends (with Martin Clunes, Peter Capaldi and Jane Horrocks in the cast at Hampstead Theatre) won the Evening Standard and Critics’ Circle Awards for Most Promising Playwright. There followed The Clink (1990) for Paines Plough, for whom he was Arts Council Writer-in-Residence from 1987–89; A Going Concern (Hampstead, 1993); and The Libertine, a considerable success at the Royal Court Theatre in 1994, where he began an eleven-year stint as Literary Associate, which brought him into contact with a whole generation of emerging writers. He also began giving writing workshops at the Court, which were attended by then little-known playwrights such as Simon Stephens, Roy Williams and April De Angelis.

The American premiere of The Libertine, directed by Terry Johnson at Steppenwolf Theatre, Chicago, in 1996 with John Malkovich as Rochester, led to an ongoing association both with Malkovich and with Steppenwolf, where Lost Land, about Hungary at the end of World War One, was premiered in 2005, again with Malkovich in the lead. When The Libertine was made into a movie (released in 2005) starring Johnny Depp, it was Malkovich’s company that produced it.

Rosamund Pike (Elizabeth Malet) and Johnny Depp (Rochester) in the 2004 film adaptation of Stephen Jeffreys’ play The Libertine, for which he also wrote the screenplay

Meanwhile, Stephen wrote I Just Stopped By to See the Man (directed by Richard Wilson at the Royal Court in 2000), a tribute to the old-time blues singers of the Mississippi Delta, which was also staged by Steppenwolf and many other American theatres; and Interruptions (written while resident at the University of California, Davis, and staged there in 2001), which sprang from his fascination with the Japanese aesthetic principle of Jo-ha-kyu and his desire to create a particular narrative form to express our struggles with democracy and leadership. The Art of War (Sydney Theatre Company, 2007) was inspired both by the ancient Chinese military treatise by Sun Tzu and by Stephen’s own response to the Gulf War. In 2009 he contributed the first play (Bugles at the Gates of Jalalabad) in the series The Great Game: Afghanistan at the Tricycle Theatre, London. This landmark series toured to the US and was performed to senior military personnel at the Pentagon.

Throughout his career, Stephen kept up a steady stream of adaptations. One of the earliest, in 1982, was of Dickens’s Hard Times for Pocket Theatre Cumbria. Two years later came Carmen 1936 for Communicado, which won a Fringe First and played in London at the Tricycle Theatre. He adapted Richard Brome’s seventeenth-century comedy, A Jovial Crew (RSC, 1992), and, in 2000, The Convict’s Opera (premiered in Australia at Sydney Theatre Company and in the UK by Out of Joint), based on The Beggar’s Opera but set on a convict ship heading for Australia. In 2011 his stage adaptation of Backbeat, Iain Softley’s film about The Beatles, opened in the West End, while his characteristically witty and erudite translation in 2013 of the libretto of The Magic Flute in Simon McBurney’s radical production has been performed all over Europe. And for the RSC he helped adapt their 2016 production of The Alchemist.

The Sydney Theatre Company and Out of Joint production of The Convict’s Opera by Stephen Jeffreys

As well as the one for The Libertine, Stephen’s other screenplays include Ten Point Bold, a love story set against the tumultuous political background of the Regency period, written in 2003 but so far unfilmed, and the biopic Diana, released in 2013, directed by Oliver Hirschbiegel and starring Naomi Watts as the Princess of Wales.

Ever since his experience as a selector for the annual NSDF, which involved him in mentoring and launching many careers, Stephen was steeped in the practicalities of theatre and relished collaborative creative relationships with young companies and young playwrights. He was also the ‘go to’ person for short celebratory plays for leaving dos, birthdays, weddings, etc., all of which made him a hugely popular and enormously well-liked figure in the theatre community.

Publisher Nick Hern pays tribute to Stephen Jeffreys…

My relationship with Stephen dates back thirty years, initially as his publisher, latterly as a friend. A nicer man and all-round gent you couldn’t hope to meet. Also a brilliant and inspiring teacher.

Having sat in on one of his famous writing workshops at the Royal Court, I immediately commissioned him to write a book. That was twenty years ago, but whenever we met in the intervening years – usually at Royal Court press nights with him in his trademark hat – he would assure me that progress was being made. When he got ill, progress suddenly became a matter of urgency.

The book was still incomplete – though in its final stages – when he died, and his friends and colleagues and above all his widow Annabel Arden are striving to complete it. Playwriting – Structure; Character; How and What to Write will be published in the next few months to sit alongside a volume of collected plays which came out in July.

Dear Stephen: he will be much missed by this country’s playwriting community as well as, of course, by audiences of the brilliant plays he wrote, and those – tragically – he never got to write.

All of us at Nick Hern Books are greatly saddened by the loss of Stephen Jeffreys. We’re incredibly proud to publish his work, and our thoughts are with his family at this difficult time.

Photograph of Stephen Jeffreys by Martin Argles.