Pursuing a career in the arts brings unique pressures and demands – and in order to navigate them, it’s important that performers and creatives develop techniques to maintain good emotional wellbeing.

In this extract from their new book Developing Your Emotional Health: The Compact Guide, authors and mind coaches Andy Barker, Brian Cooley and Beth Wood discuss the impact stress can have on performers (both positive and negative), and some steps you can take to address it when it arises.

Being a performer can be a stressful profession, with every choice laid out for public scrutiny. To create artistic work that is worthwhile we must dig deep, drawing upon our most intimate experiences and fragile resources, and then we must be prepared to take all criticism impersonally once we have laid ourselves bare to strangers and our performance becomes the topic of discussion.

The list of situations that cause performers stress is extensive – from coping with stage fright and audition nerves (and then, of course, the week spent waiting to hear if you’ve got the job) to the anxiety related to getting the next one. Add to this the financial instability and the lack of clear career progression, and it’s a heady mix that is highly likely to be impacting your emotional health.

However, it is not the situation itself, but our level of resilience and our response to the situation that determine our level of stress and ultimately the consequence. And as performers well know, a certain level of stress can be harnessed for a good purpose.

Performance Buzz

From the time of our first school play, we understand that our pre-show nerves, the adrenalin, are a necessary ingredient of a focused and energised performance. In fact, many actors report a sense of confusion and even distress when they are ill or exhausted and suddenly without the nerves that would usually power them into the show.

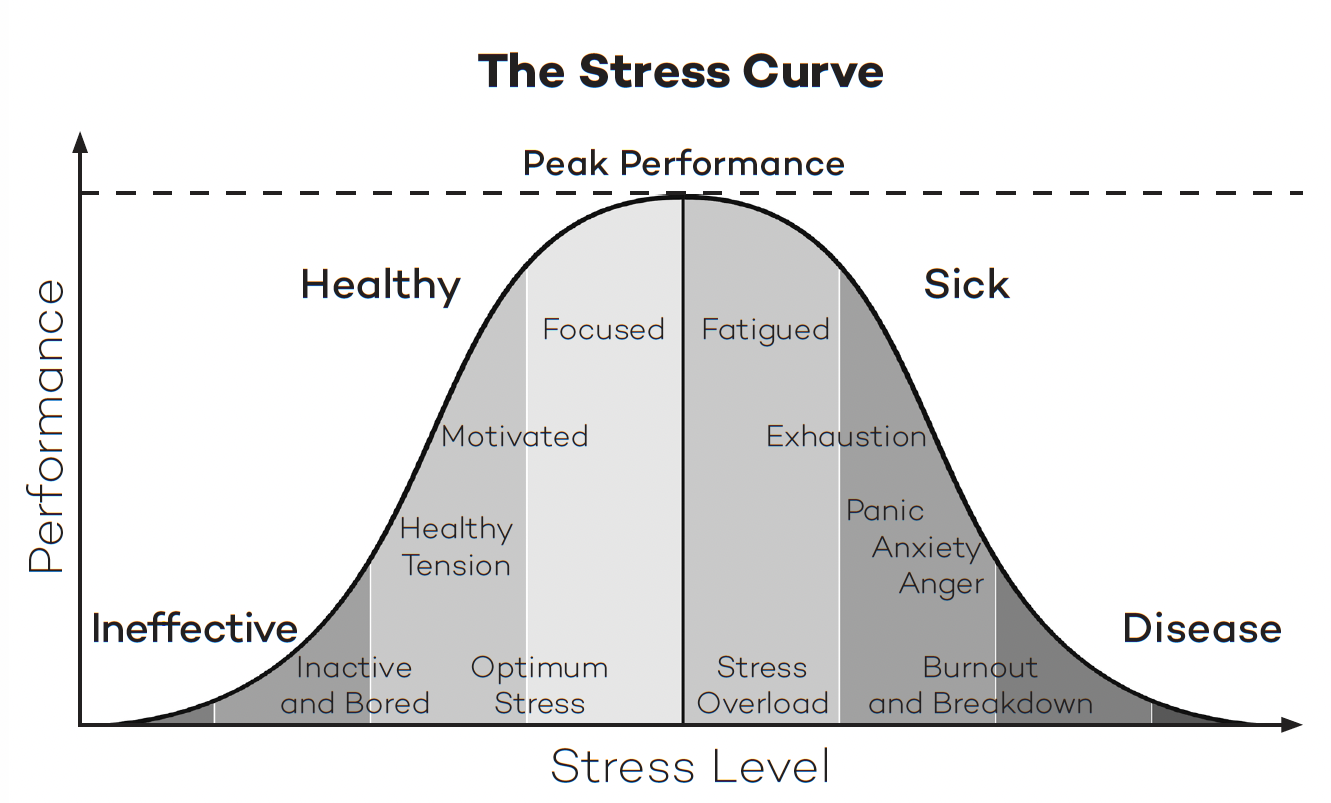

Humans need a certain amount of pressure to be fully engaged, to approach a task with full concentration. And to feel this pressure, first we must care. We must have an emotional connection with the task. It is why long runs of a production can take us to the bottom left of this chart.

This bell curve clearly shows the place where we can deliver the optimum performance: right in the middle. Too far to the left on the graph and you are not fully engaged. Too far to the right and you are tipping into chronic stress, exhaustion and patterns of mental and physical ill-health. In fact, prolonged chronic stress can be fatal.

It seems clear that if you want to deliver your best performance, it is key to ensure that you are operating at the top of the curve – or as close to it as possible.

Of course, our levels of stress – and our performance buzz – are just as important to our daily lives as they are to our performances. One of the things that tends to happen with performers is that you may sense this increasing pressure, but you are in a state of creative flow and do not want to let go of the buzz. But it’s vital that you do.

The Stress Response: Fight or Flight

Here’s why. If you draw an imaginary line into your brain from your eyes and another from your ears, the two places these lines intersect in the brain each side is called the amygdala. In normal circumstances the job of the amygdala is to pass sensory information up to the prefrontal cortex, the higher-thinking brain. But in times of perceived threat or danger it has another function: it initiates the ‘fight or flight’ response.

Most people can probably think of what this feels like. There is a surge of adrenalin (and other chemicals) through your body that gives you enough physical energy and strength to fight a wild animal should it be hurtling towards you, or to turn and run.

This instinctive response has served humankind pretty well through its evolutionary development. However, our brain works on a system of threats and rewards. If it senses a threat, then the ‘fight or flight’ response will kick in, even if it is simply one of the many commonplace stressful situations of modern life. And once the ‘fight or flight’ response kicks in, then the amygdala no longer passes information up to the higher-thinking brain. At the times when you most need to be thinking clearly – when you’re problem-solving, decision-making, or during an interview or audition – you simply can’t.

A key part of developing your resilience is knowing how to address stress when it arises, without falling back on a ‘fight or flight’ response. Here’s a step-by-step process for you to practise when it next happens:

1) Recognise the signs of stress.

It might be a churning feeling in your stomach or a general increase of tension through the body; perhaps a clenching of the jaw or pain between your eyes. There’s myriad ways that stress will affect each individual. Try to identify the physiological symptoms that come most often to you.

2) Step away from your own signs of stress.

It’s helpful to have a mindfulness exercise that you can go to whenever you need to bring yourself quickly out of the ‘fight or flight’ response. An example exercise is included at the end of this post, and you can find many more in our book Developing Your Emotional Health: The Compact Guide – so choose the one that you like best or that you find calms you most easily. Do this exercise several times a day if you can, in order to train your brain to default to this exercise and the calmer state when required, without effort or conscious choice.

3) Look at the stressful situation and accept it.

Consider the events that led to the stress. Concentrate on the ‘what’ rather than the ‘why’. What happened? Look objectively, without remorse or any other emotional response, and, most importantly, look without judgement. You cannot accept if you are judging.

4) Commit to change.

Know why this is a situation that you want to do something about. Relate it to your meaning if you can. On a scale of 1 to 10, how much do you want this change? (Remember we can want the ‘small things’ a great deal – for example, to eat more healthily or to be on time.)

5) Make a positive affirmation and speak it out loud.

For example: ‘I can choose how I respond to this situation’, ‘I can make my diet healthier’, ‘I can improve my punctuality.’ Say this out loud as many times as you can in a minute.

6) Imagine a positive future.

Humans are predisposed to creating negative mental movies of all the things that could possibly go wrong. Creative people, of course, tend to be especially good at this self-torment! But we can use the same creative abilities to our positive advantage. Imagine yourself in three, four or five years’ time (as feels best), having entirely solved this problem. What does this look like? And, more importantly, feel like?

7) Always congratulate yourself.

A very important habit to adopt and nurture is giving yourself credit for overcoming a stressful situation, for solving it, or at least for taking a big step in the right direction. In life, generally we so often miss the moment when something has worked. Performers are often criticised for being in love with applause or success. We have rarely found this to be the case. In fact, on the contrary, there is a real tendency to breathe a sigh of relief at the end of a run rather than giving yourself an enormous pat on the back and properly reflecting on a job well done. If we are to walk towards a state of better emotional health, it is certain that we must all work harder to recognise and celebrate our successes.

* * *

Remember that stress depends on your perceived ability to cope with an event or situation. The way that you choose to respond is in your control. In fact, there is research that takes this even further, suggesting that those who have physical symptoms of medium to high stress but do not believe that this will damage them – instead seeing it as their body preparing to help them deal with the situation – do not go on to suffer.

If we choose to see a situation, however difficult, as a challenge to be overcome, then to a very large extent our brain responds accordingly and delivers the chemicals and hormones to help us in the task. Never has the maxim ‘We can do it if we put our mind to it’ been more true.

As a performer, you are in a very strong place to make changes that will positively impact your mental and emotional health. It is likely that you already have heaps of resilience, creativity and compassion. It is just about making sure that, as well as being the tools of your trade, they are tools that will help you to build a calmer and happier life for yourself.

If you’re ready to begin this journey of self-development, in Developing Your Emotional Health you’ll find lots of tools and techniques – like the example exercise below – to help you on your way. You chose this profession because it is extraordinary – and you are extraordinary. So, enjoy it. Take these techniques and embed them into your life. Aim high. Now is the time to stop the self-sabotage and to unlock your true potential.

Sample Exercise: Foxhole in Your Mind

[A quick note: this exercise, like others in the book, involves a guided audio clip – you can access this via the player below.]

This exercise is similar to the Russian theatre director Stanislavsky’s sense memory exercises, which you may be familiar with.

- Imagine a place that is both safe and beautiful. This is your own personal foxhole. I have recently changed my own safe space from an underwater Egyptian city to a place in the Peruvian jungle that I was lucky enough to visit recently. It can be a place you know well, a location from a book, film or game, or simply a place conjured from your imagination.

- Visualise as much detail as you can – the shades of colour, the textures or smells, the temperature, the qualities of sound.

- When you are ready, place yourself into the setting, imagine yourself moving through the physical environment.

- What can you see in your near and peripheral vision? Is it warm or cold? Are the smells strong or subtle? What does the air feel like against your skin?

- After two minutes, open your eyes.

- Make a note of your safe and beautiful place – and how it made you feel. Or draw it.

This exercise works very quickly to slow down your heart rate and lower your levels of cortisol. With practice, your foxhole becomes a place that you can escape to whenever you feel the ‘fight or flight’ response start to kick in. If you do it enough times you may well be able to beat the symptoms of the stress response.

This is an edited extract from Developing Your Emotional Health: The Compact Guide by Andy Barker, Brian Cooley and Beth Wood – out now, published by Nick Hern Books. Get your copy direct from the NHB website here.

Andy, Brian and Beth have all worked in the arts in various roles, including as actors, writers, directors and stage managers. Together, Andy and Brian run Mind Fitness, an organisation dedicated to developing mental health, wellbeing and business effectiveness, and Beth is Artistic Director of Prospero Theatre Company, an inclusive, award-winning theatre company that uses drama to improve the quality of life for adults and young people with disabilities and mental-health conditions.