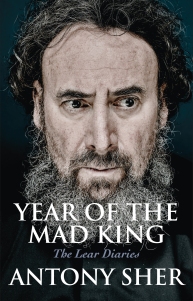

Leading actor Antony Sher’s new book Year of the Mad King: The Lear Diaries provides an intimate, first-hand account of his process researching, rehearsing and performing arguably Shakespeare’s most challenging role, Lear, in the acclaimed 2016 Royal Shakespeare Company production.

Leading actor Antony Sher’s new book Year of the Mad King: The Lear Diaries provides an intimate, first-hand account of his process researching, rehearsing and performing arguably Shakespeare’s most challenging role, Lear, in the acclaimed 2016 Royal Shakespeare Company production.

This extract, written during rehearsals only a few weeks before the production opened, takes us behind the scenes of the RSC, offering a window on director Gregory Doran and the cast’s sharp, insightful interrogation of the text – and how events occurring in the world outside fed into the production. Also included are a selection of Sher’s magnificent illustrations, which feature throughout the book.

Thursday 7 July 2016

When I walk into the rehearsal room this morning, I find one wall transformed. Covered with sheets of paper: some with images, some with text. It’s the research that Anna [Girvan, assistant director] has led, about the homeless in Shakespeare’s time. Much of it is from two books by Gamini Salgado: The Elizabethan Underworld and Cony-catchers and Bawdy Baskets.

Reading the extracts, I learn that the failure of harvests in the 1590s, and subsequent shortage of food, led to the Enclosure Acts, where people were thrown off common land and deprived of their livelihoods. Some turned to petty crime, while others took to roaming the countryside.

This is the population that Greg [Doran, director of King Lear and Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company] wants to represent, as a kind of chorus, in the production.

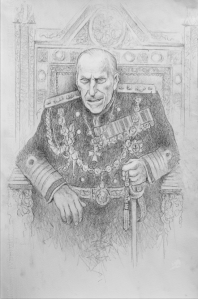

Prince Philip’s Lear

I go over to my bag, find a picture, and stick it up among the others on the wall. It’s the one of Prince Philip which I sketched about a year ago – showing him in some kind of discomfort during an official ceremony.

Good. Now the display shows both sides of the world we’re trying to create. The poor naked wretches and the burden of monarchy.

Oddly, both sides represent the Dispossessed.

Odder still, Lear has brought it on himself.

In rehearsals of the storm scenes, I confessed that I didn’t know what to do with ‘Blow winds’. I said, ‘Let’s take the reality. A man is shouting in a storm. You wouldn’t be able to hear him. He probably wouldn’t be able to hear himself. We’ve solved how to do it in performance – we’ll be using mics – but how do we rehearse? I can’t just stand here, yelling. I’ll strain my voice.’

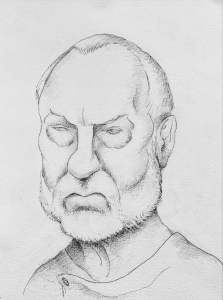

Derek Jacobi as Lear

I mentioned the brilliant solution which Michael Grandage and Derek Jacobi found in their 2010 Donmar production. When you first saw Lear in the storm, you heard the full cacophony of it. But as he lifted his head to speak, all the sound was abruptly cut, and he whispered the speech: ‘Blow winds…’ It was, as Lear describes in his next scene, ‘The tempest in my mind’.

‘Couldn’t we borrow that?’ I suggested tentatively.

‘Absolutely not,’ said Greg; ‘Much too recent. And anyway, that was a chamber-piece production and that was a chamber-piece solution, and we’re not doing a chamber-piece.’

He then came up with his own, striking scenario for the scene. He suggested that maybe the winds aren’t blowing – yet – and the speech is a desperate plea (‘Blow winds, I beg you!’), not simply a description of what’s already happening (‘Yeah, go on winds, blow!’)…

…And so we created a narrative to the speech:

- A subsidence in the storm prompts, ‘Blow winds…’

- A flash of lightning prompts, ‘You sulphurous and thought-executing fires…’

- A crash of thunder prompts, ‘And thou, all-shaking thunder…’

We can put these cues into rehearsals, we can create the other character in the scene – the storm – for me to play against.

Stage management made precise notes: they’ll find some recordings from stock (for now) to play when we next rehearse the scene.

For me this was, potentially, a solution to the hardest part of the role.

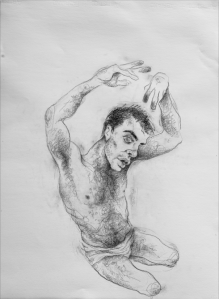

Olly as Edgar as Poor Tom

Then we moved onto the first Poor Tom scene. Oliver Johnstone [playing Edgar] really went for the mad tumble of language in his speeches. (It’s not just Beckett who owes a debt to Shakespeare, it’s James Joyce too.) I was also intrigued to note that Olly had a new range of movements – some of them twisted and jerky, almost like cerebral palsy – and new sounds too: mumblings and stutters. This was all from his ‘secret’ rehearsals with Greg. Which is a technique Greg used with the witches in Macbeth. He’d work with them privately, so that we, the rest of the cast, never knew what they were thinking or what motivated them. It made them more mysterious, more powerful.

I think, in fact, it’s originally a Mike Leigh method. I experienced it when I did his stage play Goose-Pimples (1980, Hampstead and Garrick). Each of the characters was developed separately, in one-to-ones with Mike, so that when he started to bring us together and create a storyline, we encountered one another as strangers. After all, in real life you know little or nothing about people you meet for the first time.

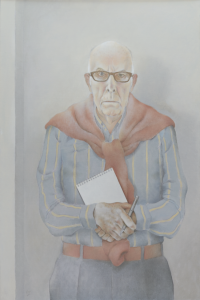

The Minimalist (Richard Wilson directing)

I remember that the long Goose-Pimples improvisations, and later the equally long Auschwitz exercises that Richard Wilson devised to rehearse Primo (2004, National Theatre and Broadway) can make your head go to a very funny place. I was angry with both Mike and Richard after the sessions – because of where they’d taken me – yet my anger was totally unjustified: I could’ve stopped at any point, and walked away. Except I couldn’t, really – it becomes a kind of self-hypnosis.

Today, I wondered how much Edgar loses himself in the Poor Tom disguise? But, of course, I wasn’t allowed to ask.

Olly had a question for me though, in the mock-trial scene: had Lear been planning this cross-examination for a while, ever since his daughters turned against him after the abdication?

‘That’s an interesting thought,’ I said; ‘There must’ve been people yesterday…’ (when the Chilcot Inquiry into the Iraq War was published) ‘…who’ve become obsessed with the idea that Tony Blair should be put on trial for… what’s it called?… humanity… what’s the phrase?’

Someone suggested, ‘Crimes against humanity?’

‘Exactly!’ I cried; ‘That’s what Lear has been obsessing about. Except in his case, it’s crimes against the king!’

This is an edited extract from Year of the Mad King: The Lear Diaries by Antony Sher, published by Nick Hern Books.

This is an edited extract from Year of the Mad King: The Lear Diaries by Antony Sher, published by Nick Hern Books.

Get your copy of the book for just £12.74 – that’s 25% off the RRP – by entering code SHER25 at checkout when you order via our website.

The RSC’s production of King Lear transfers to BAM, New York, from 7-29 April, before returning to Stratford-upon-Avon from 23 May – 9 June.

Illustrations by Antony Sher, photographed by Stewart Hemley. Author photo by Paul Stuart.