Mike Bradwell – who died earlier this month at the age of 77 – left an indelible mark on British theatre. During his long and illustrious career as a theatre director, he founded, worked with and ran a variety of leading companies and venues, and gave early chances to many young playwrights who have gone on to enjoy great success.

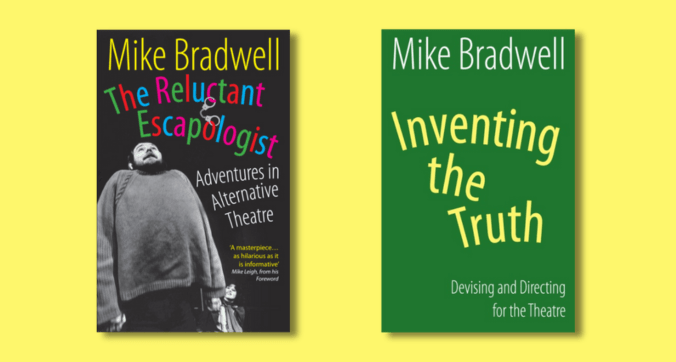

Bradwell was also a skilled writer, and Nick Hern Books is proud to publish his books The Reluctant Escapologist: Adventures in Alternative Theatre (2010, winner of the Theatre Book Prize) and Inventing the Truth: Devising and Directing for the Theatre (2012), as well as many playwrights whom Bradwell directed and championed.

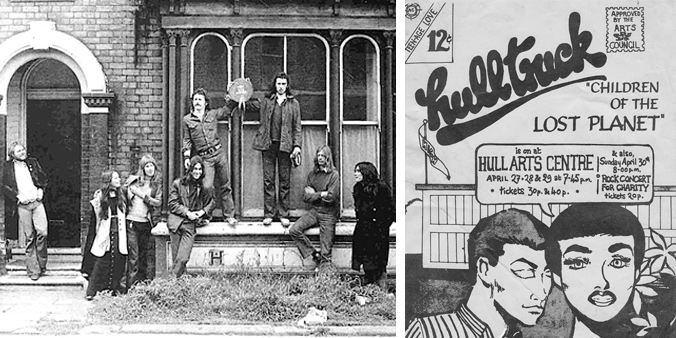

Here, to mark the sad occasion of his passing, we share an extract from Bradwell’s award-winning autobiography The Reluctant Escapologist, telling the story of the unlikely formation of Hull Truck Theatre. And NHB’s founder and publisher, Nick Hern, pays personal tribute to a theatre-maker with ‘a sure eye… [whose] like we shall not see again’.

This is an edited extract from The Reluctant Escapologist by Mike Bradwell.

Hull Truck was called Hull Truck because we lived in Hull and travelled about in a truck.

John Lee and Richard Cameron, two mates I’d made during a year studying Economics at Doncaster Technical College before I went to East 15 acting school, had both moved to Hull. John was at the University of Hull’s Drama Department and Richard was training to be a teacher. Throughout my time at East 15 I had made occasional forays to Hull to run workshops for the East Riding County Youth Theatre and to attempt to impress female drama students with my metropolitan sophistication. I’d had many late night stoned conversations with John about starting a touring theatre company, and Hull seemed the place to do it. Hull was cheap, it was easy to get the dole, and it was the last place on earth anyone in their right mind would go to found an experimental theatre troupe.

The idea was originally to have a company that made theatre for people of our own age about people of our own age. We would create plays through improvisation about characters that were familiar to our audience living in situations and relationships that they recognised. I felt that there was a whole generation whose stories were not being told in contemporary theatre, or, at best, they were being stereotyped. Every time you saw a student on stage or television they would be wearing a duffel coat and a college scarf. Stage hippies, if there were any, would wear beads and sandals and flash peace signs.

Our company would tour universities, colleges, theatres, arts centres and arts labs. The audience we were after were the Rolling Stone readers, the people who would go and see a rock band, but not necessarily a play. To counteract this Hull Truck plays would have music, and the company would also function as a band. This was probably as much to fulfil all our Grateful Dead and groupie fantasies as anything else, but the notion was to provide a live soundtrack that would complement and comment on the action. We claimed that our two big influences were Chekhov and Bo Diddley. We planned to be a nuisance.

The company would be a collective in as much as everyone would be paid the same, which was nothing. Everyone would sign on when they got to Hull and hope that Social Security wouldn’t find them a job. In Hull there was not much risk of that. The DHSS did more to subsidise arts in Britain than the Arts Council ever did. As a touring company though, we would need a van and some props so we set out to raise money. I cashed in some Premium Bonds. We bought some headed notepaper and stamps and wrote to rich and famous people for help.

B.A. Young gave us five pounds. Harold Pinter declined. Tony Garnett gave us a tenner. George Melly advised us to go to the Arts Council. Donald Pleasence gave us a fiver. Jonathan Miller and Albert Finney said they were broke. The London Rubber Company, makers of Durex, wished the venture every success, and John Cleese told us to fuck off. In all we raised about eighty pounds, most of which went on writing to another bunch of rich and famous people who didn’t give us anything.

***

The first person to audition for Hull Truck was a young Northern Irish actor called Gerard Murphy. He couldn’t play an instrument but we offered him the gig anyway. He turned us down for the Glasgow Citizens’, who paid wages. He went on to be a magnificent Henry V for the RSC and to have a long and distinguished career. Next was a guy called Brian Routh, who played the harmonica. He brought along his

friend Martin von Haselberg. They had both been thrown out of East 15 for being experimental. Brian was fine, but Martin was clearly nuts. Halfway through the audition they both lay on the floor, waved their legs in the air and shouted ‘Kippana! Kippana! Look at you getting all high and mighty. Whoops Kippana!’ They explained that they had a collective alter ego called Harry Kipper who occasionally took over. It

was all part of their act. They called themselves The Kipper Kids. We asked Brian to join but he didn’t want to break up the winning team. The Kipper Kids went to New York where they became successful and highly regarded performance artists. Martin von Haselberg turned out to be a German Baron. He married Bette Midler.

I landed a gig fire-eating for Led Zeppelin’s show Electric Magic at the Empire Pool Wembley. We spent my fee on a company publicity brochure. We decided to call our first show Children of the Lost Planet. In it we promised to reveal the truth about ‘the new, permissive, anarchist, drug-crazed, long-haired, Communist, hippy student love culture’.

We persuaded the Drama Department to let us open our show in their brand new Gulbenkian Centre. Opening night would be 10 March 1972.

***

We moved to Hull on 18 December 1971. It was the coldest place on earth. We rented a semi-derelict house in Coltman Street off Hessle Road near the fish docks in the poorest area of town. The rent was six pounds a week. We had three rooms on the second floor plus a kitchen, a bathroom and a windowless attic that we planned to use as a rehearsal room. Most of the ground floor was boarded up and stacked with broken furniture. There were feral cats. At the back lived Mr White, a solitary man from Sunderland who played Jim Reeves records all day and sometimes all night. There was a solitary fan heater. The house backed on to a wasteland where the rag and bone men grazed their horses. Outside the house was a phone box. For the first year it was our office.

On 9 January 1972 rehearsals began. The original idea was that we would meet every morning at eight in the upstairs attic for a warm-up. Another member of the company – a Canadian girl called Lisa Hicks who wrote sensitive folk ballads and was into the kabbalah – taught yoga classes and I did East 15 Laban exercises. The days would initially be spent in one to one character work and research, and in the evenings we would rehearse as a band. Several things became obvious straight away: half the company were incapable of functioning in daylight; the attic studio was unusable because it had no windows and the feral cats shat in it; and the music was going to be magnificent.

Before long it was the middle of winter and snow was on the ground. We rehearsed in one of the rooms burning broken furniture and banisters in the fireplace. We ran out of firewood so built a tent of blankets and rehearsed under that until it collapsed and blew up the fan heater.

To cheer ourselves up we played a music gig at Hull Arts Centre as part of a fundraiser for a local homeless charity. Alan Plater heard us and became a great fan and supporter. The rest of the Arts Centre staff regarded us with deep suspicion. We were a bunch of scruffy hippies and they were real pros doing proper plays like The Lion in Winter and Little Eyolf.

After six weeks of improvisations I came up with the outline for the play. Essentially Children of the Lost Planet would be a play about a group of young people living away from home for the first time, trying to live up to second-hand notions of love and peace and understanding, and finding themselves ill-equipped to deal with what was actually happening to them. Hopefully the audience would recognise aspects of themselves in the characters on stage and try to find a better way to talk to each other.

Our roadie, Peter Edwards, decided that Hull Truck and poverty was not the life for him so went back home to Wales where there was a welcome in the valleys and a job with the BBC. He was replaced by Nick Levitt, who managed, for thirty-five pounds, to acquire an old Bedford van with an extremely dodgy tax certificate. We amassed a set made up of broken furniture and rancid milk bottles and on 10 March

1972, we opened the show.

Remarkably B.A. Young sent a reviewer from the Financial Times, who reported that the play ‘turned out unexpectedly to be a sensitive and sympathetic picture, with wit and comedy too’.

It was the only review the show ever got.

NHB’s founder and publisher, Nick Hern, pays a personal tribute to Mike Bradwell.

‘I first met Mike during his tenure of the ‘old’ Bush Theatre. It inhabited a room above a slightly disreputable pub on Shepherd’s Bush Green – Mike was always at loggerheads with the landlord as loud noise from down below would intrude into the tiny theatre. The programme of new plays he masterminded in that magical space was the best in London. He ‘discovered’ a now impressive number of first-time writers, typically including Jack Thorne, Conor McPherson, Chloë Moss, Mark O’Rowe, Charlotte Jones, Joe Penhall and Catherine Johnson, amongst countless others. Mike had a sure eye.

‘He and I used to bump into each other on the Goldhawk Road, which was where NHB had moved its office. On one of these occasions, I casually asked what he was doing, hoping to be told of his next discovery so that I could chase down the author and publish the play, as we already had with a large number of ‘Bush plays’. By way of an answer, Mike fixed me with a challenging stare: ‘I’m writing a book.’ And so, after some combative editing sessions, The Reluctant Escapologist was born. I loved that title! It seemed to distil Mike’s whole being into one resonant phrase.

‘The launch was scheduled for the ‘new’ Bush with both Mike, the outgoing artistic director, and Josie Rourke, the new one, speaking from the podium. Except that Mike had gone into one of his truculent moods and was threatening not to come, let alone make a speech. But he was persuaded – and the book went on to win the Theatre Book Prize, which was totally unexpected, given that the award was usually

for an aspect of theatre history. But then Mike’s life and career were theatre history –

and still are.

‘Mike was a great bear of a man who attracted intense loyalty from many of the actors he worked with. Despite his imposing size and unkempt appearance, he was capable of the most delicate work. We shall never see his like again.’