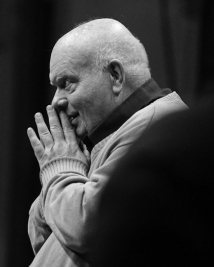

Internationally acclaimed theatre director Declan Donnellan co-founded Cheek by Jowl with designer Nick Ormerod. A focus on the actor’s art has always been central to the company’s work. Encapsulating this bold way of thinking about performance, his new book The Actor and the Space tackles the fundamental questions that face any actor, developing and extending ideas first explored in his previous bestseller The Actor and the Target. Here, he explores why acting is innate and how the relationship an actor has with their character’s context and space is what brings a performance to life.

Internationally acclaimed theatre director Declan Donnellan co-founded Cheek by Jowl with designer Nick Ormerod. A focus on the actor’s art has always been central to the company’s work. Encapsulating this bold way of thinking about performance, his new book The Actor and the Space tackles the fundamental questions that face any actor, developing and extending ideas first explored in his previous bestseller The Actor and the Target. Here, he explores why acting is innate and how the relationship an actor has with their character’s context and space is what brings a performance to life.

Human beings are actors. It is hard-wired into our DNA. From toddlers playing make-believe to old-age pensioners sharing jokes in the pub, we need to perform. It’s an essential part of being human.

Acting starts early. We use it to develop our relationship with our mothers. We watch her in wonder, mirror her smiling and repeat the sounds she makes. She intones soothing noises. We copy her. We learn things by performing for her, and she performs for us. Does that mean we are lying to each other? Of course not. Performance is woven into the fabric of our lives. It’s as natural and important to us as breathing. Performance is not merely a habit humans keep repeating across millennia, languages and cultures. It is more fundamental than that. Performance is what it is to be human. It is the operating system for life.

So, if everyone is a natural actor, what is the problem? Why can’t we all walk on stage and just act brilliantly? Well, things don’t work out so smoothly when you stand in front of an audience with an already-written text. In real life, most people can make a good stab at improvising their allotted role of father, mother, nurse, lover, and so forth. But give them a script, and their performance rapidly dies. This is the basic problem we face in a rehearsal room. There is a series of black marks on white paper, a dead thing, and we need somehow to bring it to life.

Scott Handy (Orlando) and Adrian Lester (Rosalind) in As You Like It, directed by Declan Donnellan, 1995 (photo by John Haynes)

‘Is it alive?’ is therefore a continuing question in rehearsal. Now, although we can’t define exactly what this ‘alive’ is, it becomes immediately obvious to everyone in a rehearsal room when a moment bursts into life – and it’s equally obvious when it’s dead. So where can we try to find this life? Well, we can take a tip from the experts. When scientists search for life on other planets, they don’t look for living organisms themselves. Instead, they search for the conditions that life needs: for example, in our universe, water, oxygen, carbon, and so on. They find life not by searching for life itself but instead by looking for a space that could support life.

All life depends on context, ultimately on the space around it. A child can pick a beautiful flower in the garden, take it into its bedroom and later be disappointed when it wilts and dies. When a bit older, the child will begin to understand that the flower depends on invisible things – its roots, sunlight, water and healthy earth – for life. The child is attracted by the brightness of the flower but doesn’t yet understand that, to live and grow, the flower needs a whole host of conditions which are not immediately obvious.

Everything that lives, including you and me, needs its context to bring it into life and to keep it alive. Imagine a megalomaniac inventor who wants to destroy the entire universe and leave only himself behind. He builds a mighty end-of-the-world machine. Then, when he is ready for his solo adventure, he presses the button. Hey presto! At that very moment he would indeed find that everything had disappeared. But also, at precisely the same moment, he would vanish too. He needs the world. Nothing survives in a void.

The space is the source of that precious life we are looking for in rehearsals, but we often forget it. This is not because the space is some difficult-to-grasp transcendental mystery, but because it is so utterly obvious. Edgar Allan Poe wrote a story called The Purloined Letter. Trying to recover a scandalous letter, the police tear apart a house. Their frantic and exhaustive search involves drilling holes in the wall and pulling the legs off a table to search for secret compartments.

Anastasia Hille (Lady Macbeth) and Will Keen (Macbeth) in Macbeth, directed by Declan Donnellan, 2009 (photo by Johan Persson)

But all the time, they fail to notice the obvious. The letter is in the one place they don’t think to look: it is pinned right in the centre of the wall, in plain sight. And they can’t see it for looking. Often the thing we desperately need and seek is hidden right in front of our nose.

So, what is this thing that we cannot see because it is so obvious? What is this crucial step we are missing? You and I don’t need to think about this thing, we can take it for granted, but it’s quite different when we are acting another human being. Then we cannot take the space for granted.

When a scene feels dead, our first impulse can be to throw lots of energy at it. This is normally a disaster. When the TV isn’t working, we can play with the buttons and dials all we like. We can even kick it hard, but ultimately it will never flicker into life. First, we must realise that the TV is unplugged from the electric socket. If the actor is unplugged from the space, the work cannot be alive. When actors struggle in rehearsal, they need to plug themselves into their character’s space. And they need to do that first.

Actors sometimes plunge past this first crucial step and instead valiantly throw themselves into ‘acting’, meaning each word sincerely, desperately, deeply, indicating the slightest nuance and pouring energy into the performance. They can exhaust themselves (and indeed the audience), and yet it still feels dead. The issue is rarely that they have failed to discover the right feelings, or details, or characteristics of the part. The problem is simpler: the actor hasn’t done the imaginative work to create a new and different space for the character. Yes, although the actor has no option but to be somewhere (there, in the middle of the stage, sweating), the poor character is nowhere. No effort can be alive if it happens in a vacuum. It’s not just that the character is dead; the character hasn’t even started to exist.

And this is what all the advice in my new book comes down to. It’s all about plugging into the space.

The Actor and the Space by Declan Donnellan is out now. Save 20% when you order your copy directly from our website here.