In her new book Being a Dancer, dance critic and arts journalist Lyndsey Winship shares invaluable advice and insight taken from exclusive interviews with twenty-five leading dancers and choreographers, including Carlos Acosta, Matthew Bourne, Darcey Bussell and Tamara Rojo. Here she reflects on her own personal love affair with dance, and what compiling the book has taught her…

In her new book Being a Dancer, dance critic and arts journalist Lyndsey Winship shares invaluable advice and insight taken from exclusive interviews with twenty-five leading dancers and choreographers, including Carlos Acosta, Matthew Bourne, Darcey Bussell and Tamara Rojo. Here she reflects on her own personal love affair with dance, and what compiling the book has taught her…

As a kid, I loved to dance. I did it everywhere, all the time, in public, in private. I went to classes every week without fail, for over a decade: ballet, tap and modern.

Previously, if you’d asked me why I didn’t become a professional dancer, I’d probably have said: “I didn’t have the right body.” Ballet, in particular, is notoriously prescriptive about the necessary physique for success and I wouldn’t be the only one who found they didn’t have the genetic inheritance for the job.

But since putting together my book, Being a Dancer, my answer to that question has changed. Sure, I didn’t have the natural turnout or flexibility or proportions of a Darcey Bussell or a Sylvie Guillem. But the real reason I didn’t become a dancer is because I didn’t want it enough. I wasn’t willing to put dance ahead of everything else.

Darcey Bussell, one of the contributors to Being a Dancer

Credit: Johan Persson / ArenaPAL

In the course of interviewing twenty-five successful dancers and choreographers for the book, and quizzing them about the ins and outs of their profession, from training to auditions to first nights, the abiding wisdom is that you’ll only make it as a dancer if you’re willing to dedicate yourself entirely to it. If you have to do it. If you can’t live without it. “It has to be like breathing,” Arlene Phillips told me. “I need to dance to breathe.”

Many of the dancers I spoke to were told at some point that they didn’t have the chops to make it professionally. But instead of meekly bowing their heads and hanging up their shoes, rejection only spurred them on further. Ballerina Melissa Hamilton, for example, when not accepted to the Royal Ballet School, took herself off to Greece for a year to train privately, then stormed her way to a gold medal at a major international ballet competition and straight into the Royal Ballet company. It’s that kind of single-minded tenacity that gets you on stage at the Opera House, not the fact of having beautifully arched feet.

I realise now that the real reason I didn’t become a professional dancer was because I didn’t work hard enough. I did my classes, yes, took my exams, but as Cassa Pancho, director of Ballet Black says, that’s not enough, because the physical demands of dance are so high and the competition so great. “If your leg doesn’t go high enough you need to do something about it,” she says. “Don’t wait for it to get up there – it’s not going to do that.” She recommends “floor barre, pilates, strength training, fitness training, endurance training, every day…” Say goodbye to your social life.

The discipline to work on the things you’re not good at is what marks out those who’ve made it to the top. Like West End choreographer Stephen Mear, a champion tap dancer as a teenager who turned up at dance school in London only to find he was bottom of the class at ballet and made himself do fourteen ballet classes a week until he was at the top. Fourteen classes a week! That’s a commitment most people don’t have.

Kenrick ‘H20’ Sandy, one of the contributors to Being a Dancer

Credit: Francis Loney/ArenaPAL

So I didn’t become a dancer (although I still dance all the time in private, less frequently in public these days), but as a journalist and critic I now have a front row view on the professional dance world. I speak to dancers and choreographers often and it seemed like a good idea to ask some of them to share their experiences and advice for the next generation, hence Being a Dancer. There are scores of books of advice for actors, on training, technique and auditions, but hardly anything for dancers. So it seemed like it was time to rectify that.

The book was put together relatively quickly. I did the interviews over the course of four months, grabbing people between rehearsals, sometimes for an hour over coffee, sometimes for a quick chat on the phone, grilling them about the big things – ambition, stardom, injury – and the little things – what snacks they eat, how they do their make-up, how they tie their ballet shoes, what time they go to bed. It was a huge transcribing job (every journalist hates transcription) but it was fascinating to listen back to everybody’s stories, all their very different paths to the stage, and their often differing views on the best route to success.

Dancers aren’t always asked for their opinions – that’s the result of it being a mute art form, I think – but the dancers and choreographers I spoke to for Being a Dancer were thoughtful, curious, driven people. Being a dancer at the highest level requires a unique combination of elite athleticism, military discipline, star charisma and artistic soul. But the main thing I learnt from compiling this book is that while some people might be born with talent, turning it into success is not so much about the gift, but the graft. Even if I’m too late for my own dancing career, that’s actually quite an inspirational idea.

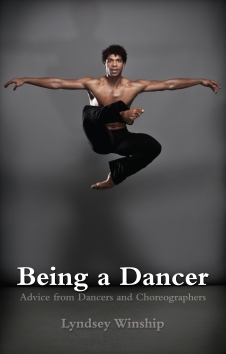

Being a Dancer: Advice from Dancers and Choreographers by Lyndsey Winship, featuring advice and insight from twenty-five leading dance professionals, is out now, published by Nick Hern Books.

Being a Dancer: Advice from Dancers and Choreographers by Lyndsey Winship, featuring advice and insight from twenty-five leading dance professionals, is out now, published by Nick Hern Books.

‘Fascinating, insightful and highly readable, this is a book to add to your collection’ – Dancing Times

Read extracts from the book on the Guardian website.